For decades, Americans were given a simple—if imperfect—rule of thumb about alcohol: moderation meant up to two drinks a day for men and one for women. It was a guideline doctors could quote, researchers could measure against, and ordinary people could use to judge their habits. That framework is now gone.

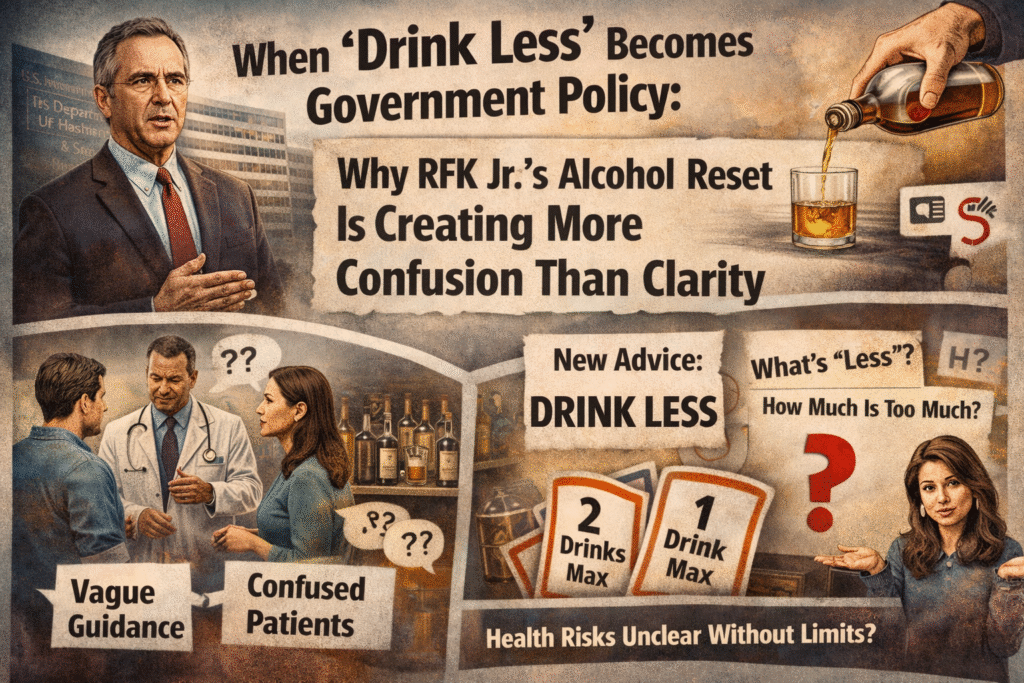

Under Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Department of Health and Human Services, federal dietary guidance has quietly but decisively shifted away from numeric limits. The new message is stark in its simplicity: drink less, or not at all—especially if you have certain health conditions. What sounds like a commonsense health nudge has, in practice, opened a policy vacuum that is leaving clinicians, scientists, and the public unsure how to translate advice into daily life.

This isn’t just a semantic change. It represents a philosophical break in how the U.S. government approaches public health communication.

Why this shift matters

Public health guidance works best when it balances scientific nuance with behavioral realism. Alcohol is a textbook example. Research increasingly shows that even low levels of drinking carry measurable risks—particularly for cancer. At the same time, alcohol is woven into social life, cultural rituals, and economic systems. Governments have long tried to manage this tension by defining “acceptable risk.”

By abandoning specific thresholds without clearly explaining risk levels, the new guidance removes the yardstick without replacing it. For millions of Americans, the question is no longer “How much is too much?” but “What does ‘less’ actually mean?”

That ambiguity matters because health advice is not absorbed in academic journals—it is acted on in kitchens, bars, clinics, and family conversations.

The science the government stepped around

What has unsettled many experts is not merely the new tone but what was left unsaid. Independent scientific committees reviewing alcohol and health found that risk begins at very low levels of consumption and increases steadily with each additional drink. Some of the strongest evidence links alcohol to multiple cancers, including breast cancer, with risk rising drink by drink.

Yet the administration chose not to formally incorporate those findings into its final guidance. The result is a recommendation that gestures toward caution while sidestepping a direct conversation about harm.

From a scientific perspective, this is a missed opportunity. If the government was concerned that numeric limits falsely implied “safe” drinking, the alternative was not silence—it was transparency. Risk curves, not absolutes, are how modern health science communicates uncertainty.

Doctors, patients, and the problem of vagueness

In clinics, vagueness is rarely helpful. Patients ask concrete questions: Is my nightly glass of wine a problem? Is weekend binge drinking worse than daily moderate use? Should I stop entirely?

The old one-to-two drink benchmark, while flawed, gave doctors a starting point. It allowed screening tools, treatment thresholds, and public messaging to align. Without it, clinicians are left to improvise, often relying on personal judgment rather than standardized guidance.

This also complicates research. Public health studies depend on definitions—what counts as moderate, heavy, or risky drinking. When the government withdraws from defining those terms, it weakens the very data systems it relies on to shape future policy.

The politics behind the policy

RFK Jr.’s broader health agenda emphasizes skepticism toward processed foods, added sugar, and what he views as entrenched industry influence. Alcohol, sitting at the intersection of powerful corporate interests and cultural acceptance, fits awkwardly into this worldview.

By framing alcohol primarily as a social indulgence rather than a quantified health risk, administration figures have signaled discomfort with regulating behavior through hard limits. But public health has always involved drawing uncomfortable lines—seat belts, smoking bans, vaccination schedules—all once controversial, all now widely accepted.

Avoiding specificity may be politically safer in the short term. In the long term, it risks eroding trust in federal guidance altogether.

What comes next

The likely outcome of this policy is fragmentation. States, medical associations, and advocacy groups will fill the gap with their own recommendations. Some will push abstinence-first messaging. Others will retain numeric limits. Americans will encounter conflicting advice depending on where they live, who they consult, and which headline they read.

Ironically, this could make alcohol policy less effective at reducing harm. Clear benchmarks don’t eliminate risk, but they make risk visible. Ambiguity, by contrast, often favors the status quo—especially in a society where drinking is normalized.

If the administration intends to recalibrate America’s relationship with alcohol, it will eventually have to confront the hard part: explaining not just that “less is better,” but how risk accumulates, who is most vulnerable, and what trade-offs people are actually making when they pour another drink.

Public health doesn’t fail because people are told uncomfortable truths. It fails when guidance is so cautious, so imprecise, that it stops being actionable. On alcohol, the government has taken away the ruler—but Americans are still expected to measure their choices.

ChatGPT